Vicious Pests

From a biological perspective, here is why targeting these three specific predators is non-negotiable for the health of our local ecosystem:

Possums are the heavyweights of habitat destruction. In our Timaru gardens and bush patches, these nocturnal browsers act like biological bulldozers, stripping the canopy of favorite trees like kōwhai, rātā, and fruit-bearing natives. By defoliating our trees, they starve our native birds of vital nectar and fruit sources. However, their impact isn’t just vegetarian; we now have extensive video evidence showing that possums are opportunistic predators that will frequently raid nests to eat the eggs and chicks of kererū and tūī. Removing them is the first step in allowing our urban “lungs” to breathe and our canopy to recover.

Rats represent a constant, ubiquitous threat to our “micro-biodiversity.” While birds get much of the spotlight, rats are devastating to the smaller, often overlooked residents of our backyards—our wētā, geckos, and skinks. They are also prolific seed-eaters, effectively “kidnapping” the next generation of our native forest by consuming seeds before they ever have a chance to sprout. Because they breed with such staggering speed, a single pair of rats can quickly overwhelm a local ecosystem. Constant trapping is the only way to keep their numbers below the “tipping point,” ensuring our native wildlife has the space to thrive rather than just survive.

Stoats are the ultimate “alpha” predator of the New Zealand bush. Small, agile, and incredibly bold, stoats are specialist killing machines capable of taking down prey much larger than themselves. Unlike many other animals, stoats have a high metabolic rate and an instinct for “surplus killing,” often killing more than they can eat. They are the primary reason many of our forest birds struggle to reach adulthood, as stoats are expert climbers that can access almost any nest. By trapping stoats, we are removing the most lethal threat from the Timaru landscape, providing a vital safety net for our pīwakawaka (fantail) and korimako (bellbird) to raise their fledglings in peace.Like flowers that bloom in unexpected places, every story unfolds with beauty and resilience, revealing hidden wonders.

Managing feral cats is perhaps the most sensitive part of our mission, but from a biological standpoint, it is absolutely critical. Unlike the companion cats sleeping on our sofas, feral cats are self-sustaining wild animals that live, breed, and hunt entirely independent of humans. They are the apex predators of our modified landscape, possessing a hunting efficiency that is almost unparalleled. Because they are larger and stronger than stoats, they can take down our largest native birds—including adult kererū and even fledgling penguins or coastal birds near our shorelines.

The impact of feral cats on our reptile populations is particularly devastating. While a rat might take a small lizard, a feral cat is a specialist at hunting larger skinks and geckos, which are often the slow-growing “engine room” of our local biodiversity. In the Timaru District, feral cats also pose a significant “pathogen risk”; they are the primary host of toxoplasmosis, a parasite that doesn’t just affect livestock but can be fatal to our native marine mammals, like the Hector’s dolphins found off our coast, when it washes into the ocean via waterways.

Biologically, we cannot achieve a “Predator Free” status by only focusing on the small mammals. If we remove rats and stoats but leave feral cats unchecked, we create a “mesopredator release”—where the top predator simply works harder to fill the vacuum, continuing the cycle of local extinctions. By humanely managing feral cats, we are protecting the entire vertical slice of our ecosystem, from the lizards in the leaf litter to the birds in the high canopy.

Top Categories

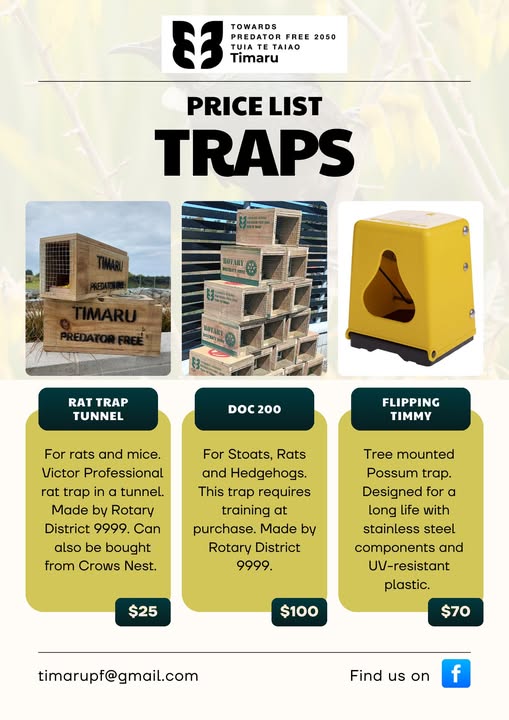

Trap Selection

2.2Kg Possum

Build Your Own